Why spectrum sharing?

Commercial access and use of spectrum has traditionally been authorized in two ways: either through individual licenses or in accordance with license exempt (unlicensed or ‘commons’) rules. It is believed much of that spectrum is lightly used or even not used. At a time when most observers believe people, organizations and businesses will need vastly more Internet and communications capacity, that is a waste of scarce resources. To move incumbent users to a new frequency band is also a very costly and time consuming proposition. Thus, spectrum sharing offers a cheaper and quicker way to maximize use of scarce resources. Shared spectrum is likely to be used in several ways in the U.S market first to support 4G, and then likely in more-intensive forms as 5G is introduced.

There is a misunderstanding of spectrum sharing according to Federated Wireless. Spectrum sharing will be applied to bands that are NOT licensed by a carrier today. The bands being explored are under-utilized bands – like those controlled by the military. The navy uses only about 1% of the spectrum available in the 3.5 GHz band at any given time. There is 150 MHz of spectrum available in this band – more than any single US operator controls at this point.

As global demand for spectrum intensifies, regulatory strategies such as these are attracting considerable interest.

Defining spectrum sharing:

“Spectrum sharing is the simultaneous usage of a

specific radio frequency band in a specific

geographical area by a number of independent

entities, leveraged through mechanisms other than

traditional multiple- and random-access techniques.”

(Quote courtesy of “Cognitive Radio Communications and Networks: Principles and Practice” By A. M. Wyglinski, M. Nekovee, Y. T. Hou [Elsevier, December 2009])

Which bands are primary candidates?

Among the U.S. bands where spectrum sharing will be key is about 500 MHz of capacity in the Wi-Fi 5-GHz band, as well as about 150 MHz in the 3.5-GHz Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) band. It is hard to see deployment happening commercially until 2018, with the likely first deployments in the United States, at 3.5 GHz. When the US demonstrates that spectrum sharing works, many other countries are looking at how to implement the same technology and tiers. Japan already uses the 3.5 GHz band, so we expect quick activity there.

In Europe, the 2.3-GHz band will be where shared spectrum first is tried. For the 2.3GHz band, the situation in Europe is complex. Even though this band has been globally identified for mobile broadband at the international level and standardized at the 3GPP, non-mobile incumbents remain the main users of this spectrum.

Spectrum sharing is also expected around the 60-GHz band, where 7 GHz is available for sharing in the frequency ranges between 57 GHz and 64 GHz, and where an additional 7 GHz of capacity is being considered for shared use.

It is also being evaluated in the licensed 71 GHz to 76 GHz band and 81 GHz to 86 GHz bands which have in the past been used for point-to-point radio links.

Who is responsible for developing spectrum sharing?

The organizations developing spectrum sharing are led by government entities (NTIA, FCC in U.S.; Ofcom in U.K.) and private entities (Google,Intel, Qualcomm, for example), instead of “standards bodies.”. The CBRS Alliance is the organization that takes the standards set by the WinnForum (Wireless Innovation Forum) and commercializes them, developing the ecosystem and a certification program. All four US carriers now belong to the CBRS Alliance.

How does spectrum sharing work? The CBRS example

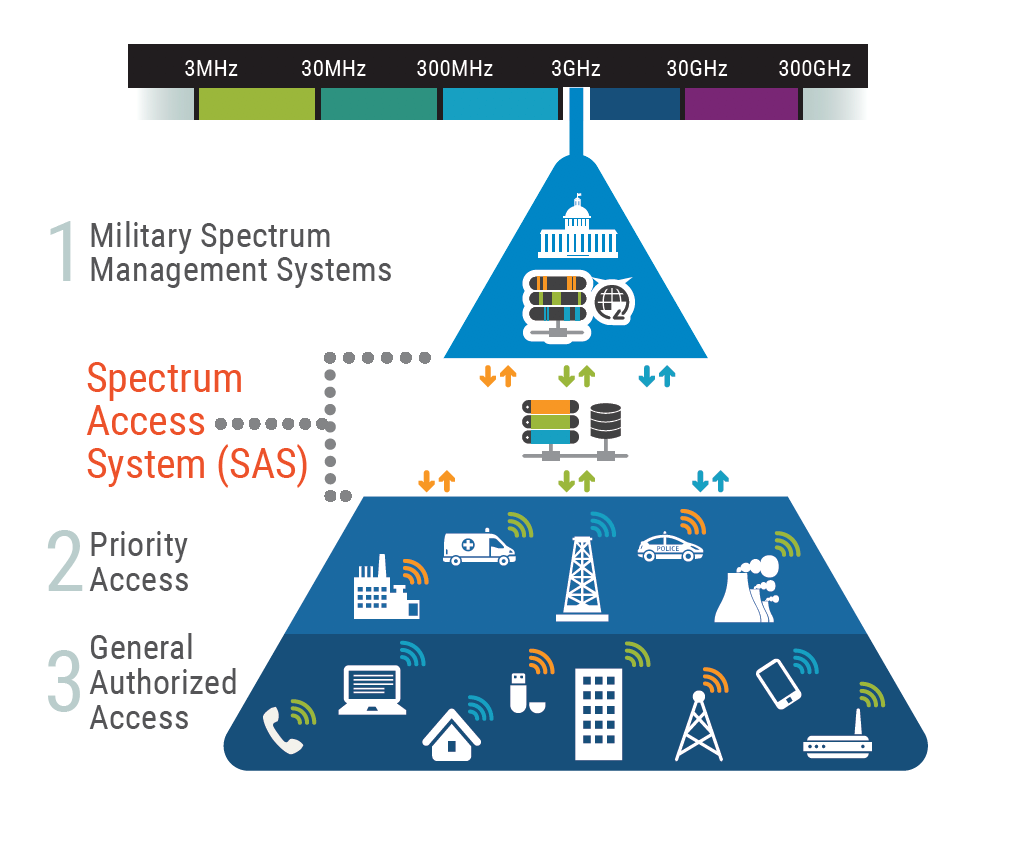

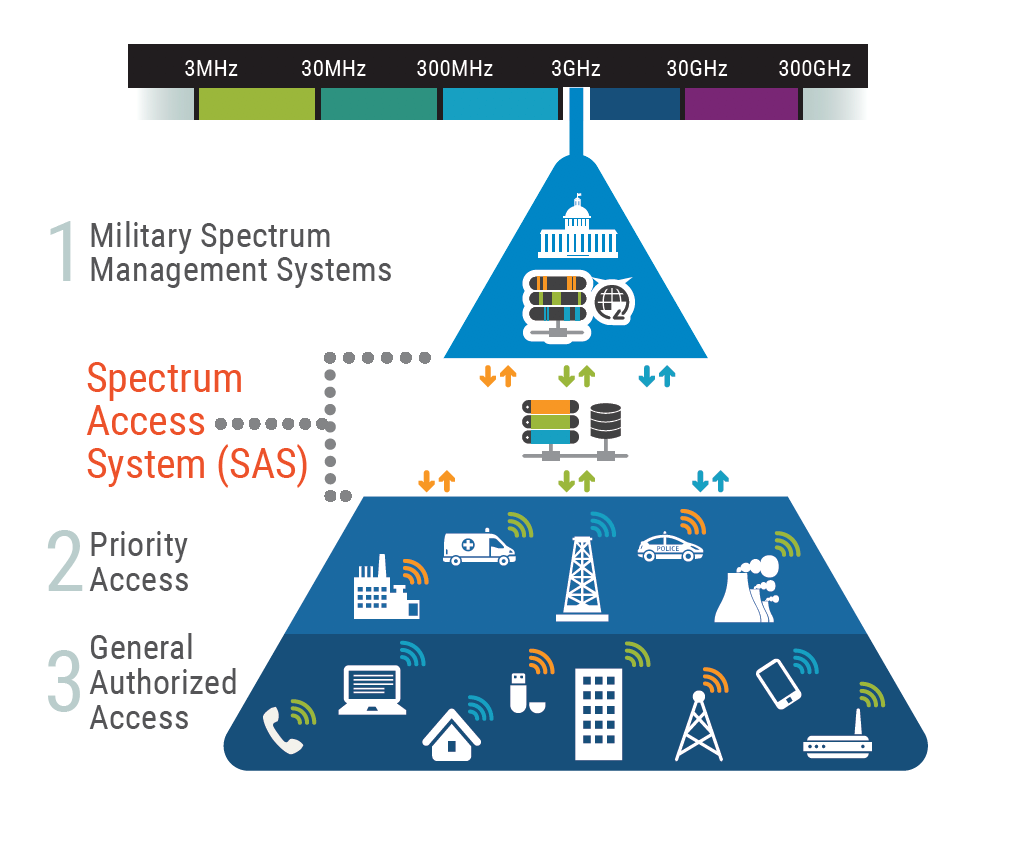

Licensing traditionally has used spatial division (different frequencies or geographies) to prevent interference. Spectrum sharing enables new deployments to use spectrum while protecting usage by existing incumbents, such as the military or satellite communication.

According to the CBRS alliance “It enables two kinds of new deployments: those that pay for a slice of the spectrum at a certain location (referred to as priority access license or PAL) and those that opportunistically use available spectrum (referred to as general authorized access or GAA). The addition of this ‘third-tier’ of general authorized deployments, where you are not required to pay for a license, means that users can employ this spectrum when it is not being used by the higher tiers.”

According to Federated Wireless, operators will be able to apply for 10 MHz PAL licenses in this band, which are location-specific. They will get second priority. That leaves 80 MHz of spectrum available for General Use, and more if no incumbent or PAL user is using the spectrum. Think of GAA spectrum like unlicensed spectrum. Carriers can use it like Wi-Fi, but so can Enterprises, property owners, venue owners, etc. CBRS radios are being added to most small cells today, and will be able to deliver LTE services over this unlicensed band, with no contention with Wi-Fi or licensed carrier spectrum.

Access and operations will be managed by a dynamic spectrum access system, conceptually similar to the databases used to manage Television White Spaces devices. The three tiers are: Incumbent Access, Priority Access, and General Authorized Access. CBRS is a bold experiment in regulation with implications beyond 3.5 GHz and beyond the US.

Courtesy of Federated Wireless

A CBRS Spectrum Access System (SAS) controls channels/frequency resources in same geographic area and time. FCC certification requires the SAS-to-SAS interoperability demonstrated by suppliers. SASs can exchange the information required to protect interference free operation by commercial and federal incumbents in the CBRS 3.5 GHz shared spectrum band. Incumbent Access users include authorized federal and grandfathered Fixed Satellite Service users currently operating in the 3.5 GHz Band.

At the end of 2016, the FCC approved seven spectrum access system administrators in the 3550-3700 MHz band: Amdocs, Comsearch, CTIA-The Wireless Association (CTIA); Federated Wireless; Google, Key Bridge; and Sony Electronics.

Spectrum Convergence

The other important development in spectrum sharing is the convergence of licensed with unlicensed bands through the bonding of mobile and Wi-Fi spectrum. Significant spectrum sharing of this type is expected to be a key feature as most devices combine both Wi-Fi and cellular connectivity.

The advent of 5G mobile networks, for example, will feature the use of “bonded spectrum” approaches such as License Assisted Access (LAA) to aggregate across spectrum types, LTE Wi-Fi Aggregation (LWA) to aggregate across technologies, CBRS/License Shared Access (LSA) to share spectrum with incumbents and other deployments. In addition, there will be new platforms such as “MulteFire” that provide quality-assured services exclusively in the 5GHz band.

What are the biggest challenges to spectrum sharing?

Challenges are partly regulatory and partly technological. In the US, The FCC and DoD needed to know that technology could be put in place to securely share spectrum while still giving access to the Incumbent users (navy and satellite) when needed, added Federated Wireless.

Success here is likely to open up other bands in the US and across the globe but some resistance can also be expected from regulators who will see spectrum sharing as lost tax revenue.

All of these developments represent a revolutionary approach to spectrum usage, moving away from command-and-control to more-dynamic allocation processes. Spectrum sharing represents a revolution in spectrum policy, a challenge to business models based on spectrum scarcity and an opportunity for business models based on sustainability for the benefit of billions of consumers.

The WBA is developing in a whitepaper an early-stage analysis of coordinated shared spectrum programs. It provides some historical background on both LSA and CBRS, contemplates the service offerings and business models that such approaches will enable, and contrasts anticipated CSS solutions with existing solutions based on traditional methods of spectrum management. Finally, the paper will suggest areas where the WBA might decide to participate as CSS solutions move from the conceptual stage into commercial reality, with a focus on identifying industry, Standard Development Organization (SDO), and Industry Trade Organization (ITO) ‘gaps’ that will need to be addressed.

About the Author

Mr. Adlane Fellah, founder of Maravedis and Wi-Fi 360 is a leading analyst in the Broadband Wireless world and authored various landmark reports on WiFi, LTE, 4G, WiMAX, Broadband Wireless and Voice over IP (VoIP). He is regularly asked to speak at leading wireless events and to contribute to various influential portals and magazines such as RCR Wireless, Fierce Wireless, 4G 360, etc. Maravedis provides market research and content marketing services to the wireless industry. Learn more at www.wi-fi360.com

Which bands are primary candidates?

Among the U.S. bands where spectrum sharing will be key is about 500 MHz of capacity in the Wi-Fi 5-GHz band, as well as about 150 MHz in the 3.5-GHz Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) band. It is hard to see deployment happening commercially until 2018, with the likely first deployments in the United States, at 3.5 GHz. When the US demonstrates that spectrum sharing works, many other countries are looking at how to implement the same technology and tiers. Japan already uses the 3.5 GHz band, so we expect quick activity there.

In Europe, the 2.3-GHz band will be where shared spectrum first is tried. For the 2.3GHz band, the situation in Europe is complex. Even though this band has been globally identified for mobile broadband at the international level and standardized at the 3GPP, non-mobile incumbents remain the main users of this spectrum.

Spectrum sharing is also expected around the 60-GHz band, where 7 GHz is available for sharing in the frequency ranges between 57 GHz and 64 GHz, and where an additional 7 GHz of capacity is being considered for shared use.

It is also being evaluated in the licensed 71 GHz to 76 GHz band and 81 GHz to 86 GHz bands which have in the past been used for point-to-point radio links.

Who is responsible for developing spectrum sharing?

The organizations developing spectrum sharing are led by government entities (NTIA, FCC in U.S.; Ofcom in U.K.) and private entities (Google,Intel, Qualcomm, for example), instead of “standards bodies.”. The CBRS Alliance is the organization that takes the standards set by the WinnForum (Wireless Innovation Forum) and commercializes them, developing the ecosystem and a certification program. All four US carriers now belong to the CBRS Alliance.

How does spectrum sharing work? The CBRS example

Licensing traditionally has used spatial division (different frequencies or geographies) to prevent interference. Spectrum sharing enables new deployments to use spectrum while protecting usage by existing incumbents, such as the military or satellite communication.

According to the CBRS alliance “It enables two kinds of new deployments: those that pay for a slice of the spectrum at a certain location (referred to as priority access license or PAL) and those that opportunistically use available spectrum (referred to as general authorized access or GAA). The addition of this ‘third-tier’ of general authorized deployments, where you are not required to pay for a license, means that users can employ this spectrum when it is not being used by the higher tiers.”

According to Federated Wireless, operators will be able to apply for 10 MHz PAL licenses in this band, which are location-specific. They will get second priority. That leaves 80 MHz of spectrum available for General Use, and more if no incumbent or PAL user is using the spectrum. Think of GAA spectrum like unlicensed spectrum. Carriers can use it like Wi-Fi, but so can Enterprises, property owners, venue owners, etc. CBRS radios are being added to most small cells today, and will be able to deliver LTE services over this unlicensed band, with no contention with Wi-Fi or licensed carrier spectrum.

Access and operations will be managed by a dynamic spectrum access system, conceptually similar to the databases used to manage Television White Spaces devices. The three tiers are: Incumbent Access, Priority Access, and General Authorized Access. CBRS is a bold experiment in regulation with implications beyond 3.5 GHz and beyond the US.

Courtesy of Federated Wireless

A CBRS Spectrum Access System (SAS) controls channels/frequency resources in same geographic area and time. FCC certification requires the SAS-to-SAS interoperability demonstrated by suppliers. SASs can exchange the information required to protect interference free operation by commercial and federal incumbents in the CBRS 3.5 GHz shared spectrum band. Incumbent Access users include authorized federal and grandfathered Fixed Satellite Service users currently operating in the 3.5 GHz Band.

At the end of 2016, the FCC approved seven spectrum access system administrators in the 3550-3700 MHz band: Amdocs, Comsearch, CTIA-The Wireless Association (CTIA); Federated Wireless; Google, Key Bridge; and Sony Electronics.

Spectrum Convergence

The other important development in spectrum sharing is the convergence of licensed with unlicensed bands through the bonding of mobile and Wi-Fi spectrum. Significant spectrum sharing of this type is expected to be a key feature as most devices combine both Wi-Fi and cellular connectivity.

The advent of 5G mobile networks, for example, will feature the use of “bonded spectrum” approaches such as License Assisted Access (LAA) to aggregate across spectrum types, LTE Wi-Fi Aggregation (LWA) to aggregate across technologies, CBRS/License Shared Access (LSA) to share spectrum with incumbents and other deployments. In addition, there will be new platforms such as “MulteFire” that provide quality-assured services exclusively in the 5GHz band.

What are the biggest challenges to spectrum sharing?

Challenges are partly regulatory and partly technological. In the US, The FCC and DoD needed to know that technology could be put in place to securely share spectrum while still giving access to the Incumbent users (navy and satellite) when needed, added Federated Wireless.

Success here is likely to open up other bands in the US and across the globe but some resistance can also be expected from regulators who will see spectrum sharing as lost tax revenue.

All of these developments represent a revolutionary approach to spectrum usage, moving away from command-and-control to more-dynamic allocation processes. Spectrum sharing represents a revolution in spectrum policy, a challenge to business models based on spectrum scarcity and an opportunity for business models based on sustainability for the benefit of billions of consumers.

The WBA is developing in a whitepaper an early-stage analysis of coordinated shared spectrum programs. It provides some historical background on both LSA and CBRS, contemplates the service offerings and business models that such approaches will enable, and contrasts anticipated CSS solutions with existing solutions based on traditional methods of spectrum management. Finally, the paper will suggest areas where the WBA might decide to participate as CSS solutions move from the conceptual stage into commercial reality, with a focus on identifying industry, Standard Development Organization (SDO), and Industry Trade Organization (ITO) ‘gaps’ that will need to be addressed.

About the Author

Mr. Adlane Fellah, founder of Maravedis and Wi-Fi 360 is a leading analyst in the Broadband Wireless world and authored various landmark reports on WiFi, LTE, 4G, WiMAX, Broadband Wireless and Voice over IP (VoIP). He is regularly asked to speak at leading wireless events and to contribute to various influential portals and magazines such as RCR Wireless, Fierce Wireless, 4G 360, etc. Maravedis provides market research and content marketing services to the wireless industry. Learn more at www.wi-fi360.com